Been in seclusion the past week to write my screenplay. It's not an easy one to write, so it's been taking a lot of my energies. I have kinda cut myself away from the rest of the world, spending almost every night in McDonald's.

There's no point telling you all that much about it since it's still in its infancy.

Sometimes, I do some heavy researches while I prepare a script (or a shoot). Do a film marathon that could help inspire me, go through books, scour through the net, do some email interviews etc. A lot of excavation is needed.

Back in July, when I started developing the idea for my screenplay, I suddenly stumbled upon a piece of information that actually rocked my world.

All the while, the only historical connection I could draw between Malaysia and Japan was the Japanese Occupation during World War 2.

I never knew that the two countries actually had an earlier relationship... apparently during the end of the Meiji Era, around 1870s to 1930s, Japanese prostitution existed in places like Penang, Sandakan, Kucing etc. Poor young women from impoverished agricultural and fishing families were sold off for prostitution in East Asia and South East Asia. They were known as the Karayuki-san (唐行きさん), many times their minds were enslaved into believing that they were serving the nation, being part of a female army. Despite being sold abroad, they continued to send money back to Japan, to their family, and also for the cause of the First Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895) and the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905). The Karayuki-san contributed much to the economy.

Until 1921, when the internationalization of Japan caused its government to consider the karayuki-san shameful, so they worked hard to bring these girls back to the country. Where they were treated with discrimination due to their previous work (and suffering) in the flesh trade, the very family members who sold them off became ashamed of them. It's a tremendous tragedy that many have forgotten.

Since they weren't talked about in public, or in scholarly discussions, this part of Japanese history was almost forgotten... until the 1972 book Sandakan Brothel No. 8: An Episode in the History of Lower-Class by Yamazaki Tomoko came out. Yamazaki managed to interview one of the last surviving karayuki-san (who happened to work in Sandakan, hence the book title), their sufferings were made aware to people again. Two years later, Director Kei Kumai's film adaptation was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film (he lost to countryman Akira Kurosawa's Russian film Dersu Uzala).

(Ironically, 27 years later, Kei Kumai's very last film THE SEA IS WATCHING (2002) would be from Kurosawa's final screenplay. I watched it last year, highly recommended.)

But I digress.

I was fascinated by the history of the Karayuki-san, so I went through numerous articles about them. They had a huge presence in Singapore back then, but remnants of them had mostly disappeared. This 2005 Japan Times article by Takehiko Kajita Singapore's Japanese prostitute era paved over is a must-read. An excerpt:

The existence of Karayuki-san in Singapore dates back to 1877, when there were two Japanese-owned brothels on Malay Street with 14 Japanese prostitutes, official Japanese data show.

Malay Street and the nearby streets of Malabar, Hylam and Bugis later grew into a big red-light district.

Singapore's official records suggest 633 Japanese women were operating in 109 brothels in 1905. The number is believed to have been well over 1,000, if unlicensed prostitutes are included.

Combined with the far larger Chinese-dominated red-light district and other similar districts catering to different ethnic groups, Singapore was known as one of the centers of the sex industry in Asia in those days.

As Singapore started to develop around the 1870s, immigrants — mostly men — rushed in from China and India to toil at rubber plantations and tin mines or as rickshaw pullers. To maintain social order, British colonial rulers tolerated prostitution at designated brothels, bringing in Chinese and Japanese women in droves.

As Japan's international profile rose with victories in the Sino-Japanese War in 1894, the Russo-Japanese War in 1904 and its having sided with the victors of World War I, Japan began to view Japanese prostitutes working overseas as a national shame.

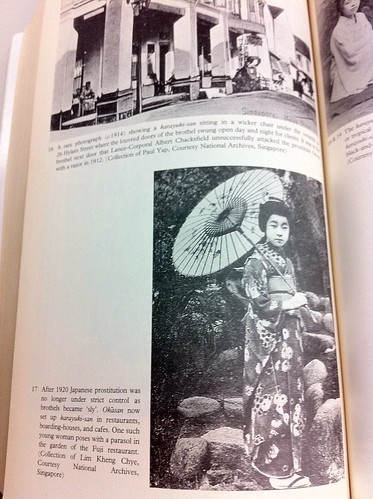

In addition, successful Japanese business operations in British-ruled Malaya, now Malaysia, lessened the need for foreign currency earned by Karayuki-san. So the then Japanese Consulate General in Singapore banned Japanese brothels in 1920.

Consequently, many Karayuki-san were forcefully repatriated to Japan. But many others managed to stay in Singapore or move to other parts of Malaya, illegally selling themselves.

Gone with the Karayuki-san is the Japanese red-light district. Ironically, the entire district is now a giant commercial complex that houses a department store run by Seiyu Ltd. and a shopping center operated by Parco Co., both Japanese companies.

Malay, Malabar and Hylam streets remain, but they are now merely passages under the roof of a structure called Bugis Junction, a popular spot with young Singaporeans that also houses movie theaters and the Hotel Inter-Continental.

Traces of Karayuki-san are more evident at Japanese Cemetery Park, where countless — and largely nameless — Karayuki-san are buried along with other Japanese.

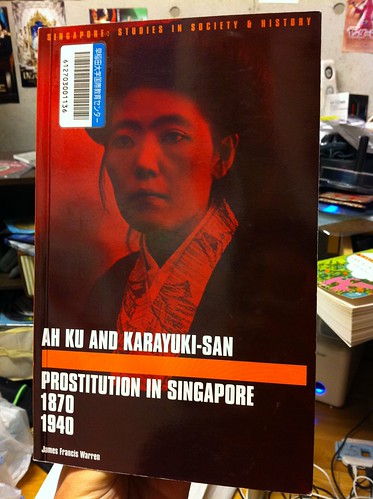

Yesterday, I borrowed the book, AH KU AND KARAYUKI-SAN by James Francis Warren, which provided a study on women who travelled from China (they're the Ah Ku) and Japan to work in Singapore as prostitutes.

It was an engrossing read which I managed to finish (speed reading) in a day. Reading through their sufferings, their daily lives, the optimism they had, the tragedies they faced, where their lives were in constant danger (many died at the hands of their clients in crimes of passion), some were driven to commit suicide (for falling in love with a client, for losing customers after ageing, for being driven too much by their handlers...). It was a dizzying read.

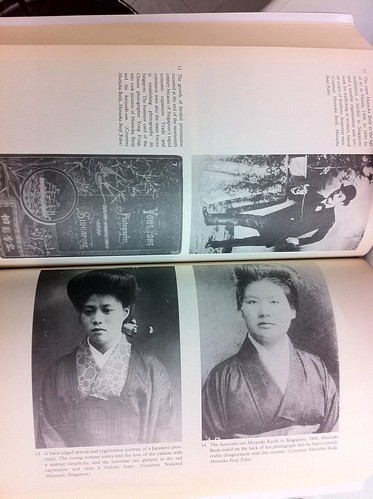

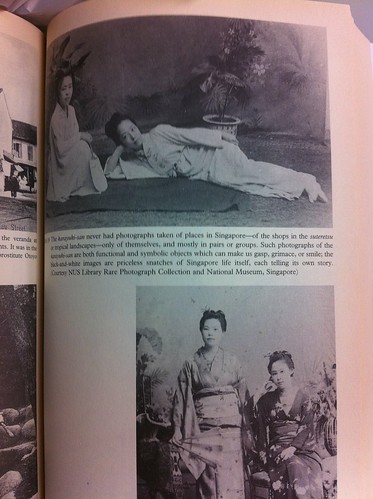

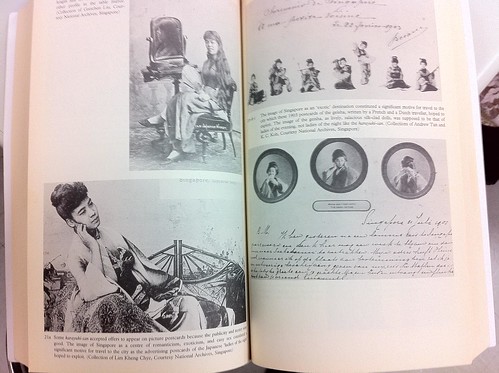

I was surprised to see that the book provided some photos of the Karayuki-san, captured during that moment. Most of the time they took the photos in groups, just so they could share the cost, the photos were often sent back to their families. There is just this indescribably tranquil beauty about these photos. The book had said that these photos probably meant more to us now than it meant to them then. These were attempts to outwit time, and allow us to catch a glimpse of a disappeared, forgotten era.

Shohei Imamura had two films related to the Karayuki-san. One is a documentary called Karayuki-san, the Making of a Prostitute (1975), the other is Zegen (1985). It's hard to acquire these two films, I'm going to try to look for them.

(UPDATED (July 19, 2016): I did. My thoughts on Karayuki-san, the Making of a Prostitute are here.)

A quote at the beginning of the book filled my heart with a faint wistful sense of melancholy.

The sound of Kikuyo Zendo's words echoed through the Japanese cemetery,

in the early morning air of a warm Singapore day, as pointing to

the deteriorating gravestone of a long-deceased karayuki-san,

she told the celebrated film-maker Imamura Shohei:

'People like this are never written up in history.'

(UPDATED (July 19, 2016): Having seen Imamura's documentary, the cemetery he visited with Kikuya Zendo seemed more to me like a Kuala Lumpur Japanese cemetery, and not the Singapore one. Too many publications and articles related to the film had erroneously mentioned that that it was mostly shot in Singapore, when to me, the locales were evidently in Malaysia)

And also, when Sandakan Brothel No. 8 writer Yamazaki Tomoko visited the cemetery of the Karayuki-san in Borneo, she noticed that the graves all faced one direction - away from Japan.

Much of Ah Ku and Karayuki-san can be read here:

UPDATED (May 12, 2014):

Thanks to one of the commenters, Bryan Ho, I learnt that a Singaporean theatre company, TheatreWorks, had done a stage adaptation of Ah Ku and Karayuki-san called Broken Birds.

Karayuki-san from M'GO Films on Vimeo.